In 1924, Haralambos Velonis, a 30-year-old vine-grower, settled in the mountain village of Manolates in northern Samos after marrying local woman Maroudio Kondyli. They moved into a late 19th-century house purchased by her father, as part of her dowry. The house bore witness to a life of fortitude and disillusionment. Today, it holds the stories of an entire village – and more.

“This house tells the story of its residents,” says current owner Nikitas Kyparissis, “but at the same time, it tells the story of the village – and, through that, the story of this eastern Aegean island.” A conservator and artisan in his late 40s, Kyparissis has spent years transforming the house into a folklore museum to showcase his growing private collection. The result of his efforts, Manolates Folk Collection – The House of Velonis, is fully open to visitors as of this season – a modest yet moving exhibition space.

“Where someone might once have simply strolled through a narrow village street, stopped for a bit, had a drink, looked around and left – they are now invited to step into a home,” he says. “Through the objects, the sounds, the smells, they can experience the life journey of the people who lived here.”

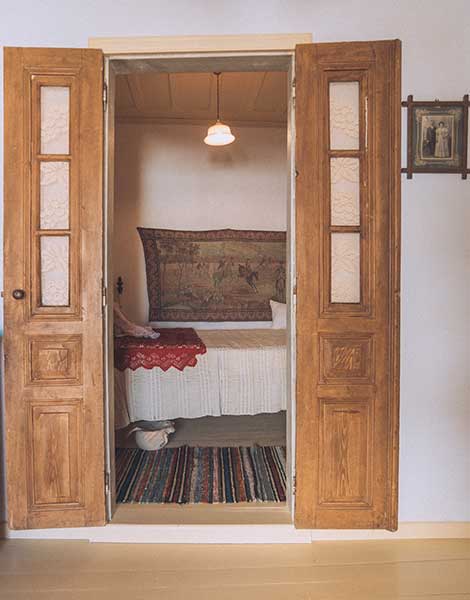

The bedroom.

The bedroom. © Nikolas Sfantos

The bedroom.© Nikolas Sfantos

The bedroom, with a traditional icon stand positioned above the headboard.

The bedroom, with a traditional icon stand positioned above the headboard. © Nikolas Sfantos

The bedroom, with a traditional icon stand positioned above the headboard.© Nikolas Sfantos

A burly man with blond hair, green eyes and a sonorous voice, Kyparissis moved to Manolates – the village where his grandmother, the local baker, was born – two decades ago; he was the same age as Velonis when he first arrived. Disillusioned with big city life, he left Athens behind. With support from his family, who sold an apartment in the capital, he was eventually able to purchase the abandoned and dilapidated property. He started by opening an eclectic souvenir shop in the basement, selling handcrafted items of his own design to make a living.

Kyparissis, an artist, activist and community leader who has become a vital presence in the village, playing a key role in reviving and celebrating local traditions, initially found himself swept up in the same wave of tourism that, over the past 25 to 30 years, had reshaped the settlement – gradually displacing vine-growing as the main source of income while eroding its traditional character. It is precisely that erosion he is now working to resist.

Nikitas Kyparissis photographed inside the museum’s eclectic gift shop.

Nikitas Kyparissis photographed inside the museum’s eclectic gift shop. © Nikolas Sfantos

Nikitas Kyparissis photographed inside the museum’s eclectic gift shop.© Nikolas Sfantos

“What pushed me to establish the museum was the deadness I felt in the village,” says Kyparissis, who is often found outside his store, playing the tsampouna – a traditional Greek bagpipe. “My grandparents’ generation is gone. My parents’ generation – the people born in the 1940s – is fading fast.” Today, Manolates has just 60 residents, less than a dozen of whom are children. “In a decade, that number will drop below 20,” he predicts. “So who will tell the stories of these people?”

Nestled in the lush, green slopes of Mount Karvounis (also known as Ambelos), at an altitude of 320 meters, Manolates overlooks the Aegean Sea and the southwestern coast of Turkey. The village began as a typical rural Samian settlement of vine-growers. First inhabited in the late 18th century, homes were usually two-story structures – families lived upstairs while the ground floor, or “katoi,” served as storage, shop space, or stables.

The living room – referred to by locals as the ’sala’ or ’ontas’ – features photographs of Velonis’ in-laws hanging above the sofa. On the chest of drawers sits the black case that once held the phonograph he brought back from the United States.

The living room – referred to by locals as the ’sala’ or ’ontas’ – features photographs of Velonis’ in-laws hanging above the sofa. On the chest of drawers sits the black case that once held the phonograph he brought back from the United States. © Nikolas Sfantos

The living room – referred to by locals as the ’sala’ or ’ontas’ – features photographs of Velonis’ in-laws hanging above the sofa. On the chest of drawers sits the black case that once held the phonograph he brought back from the United States.© Nikolas Sfantos

The museum occupies a building created by merging two adjoining houses that face the small but cozy square at the heart of the village. One half features neoclassical elements; the other bears Ottoman architectural influences, most characteristically a type of bay window called “sachnisi.” It’s a clear reflection of how the eastern Aegean island’s diverse and largely understudied folkloric identity has been shaped by its proximity to Asia Minor.

Kyparissis was fortunate to complete the structural restoration of the house just a year before Samos was struck by a 7-magnitude earthquake in 2020 – a disaster that claimed two lives and damaged numerous monuments and heritage buildings, including another folklore museum in the southern village of Koumeika. Working with meticulous care and deep affection, he revived the home’s interior – including the living room, dining room, kitchen and bedroom – restoring them to a state of arrested decline.

Visitors can now experience a carefully curated array of objects: humble kitchenware, handcrafted furniture, woven rugs, bed linens, vestments, books, family photographs and rare archival materials – including documents dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries.

“The greatest challenge,” Kyparissis says, “is how to present something that has died – exactly as it was, just before it died.”

The staircase leading to the upper floor – reserved for family life – is adorned with flower pots, a distinctive feature of Manolates.

The staircase leading to the upper floor – reserved for family life – is adorned with flower pots, a distinctive feature of Manolates. © Nikolas Sfantos

The staircase leading to the upper floor – reserved for family life – is adorned with flower pots, a distinctive feature of Manolates.© Nikolas Sfantos

Kyparissis started by opening an eclectic souvenir shop in the basement, selling handcrafted items of his own design to make a living.

Kyparissis started by opening an eclectic souvenir shop in the basement, selling handcrafted items of his own design to make a living. © Nikolas Sfantos

Kyparissis started by opening an eclectic souvenir shop in the basement, selling handcrafted items of his own design to make a living.© Nikolas Sfantos

He was deliberate about avoiding clutter. “We didn’t want to overfill the space. That would have undermined the feeling of a modest, provincial home,” he explains. “When electricity first came, there was just a wire, a socket and a bulb – maybe a proper fixture only in the ‘good’ room. It was all about function, not design.”

“If I start adding fixtures or covering the walls with photos, I distort the truth. The walls were mostly bare – we had exactly seven framed pieces, each in its rightful place. This is not a storeroom of miscellaneous objects. Everything must serve a purpose.”

Preserving what matters without tipping into excess is a delicate balancing act. But perhaps what resonates most is the realization that the once-dismissed everyday objects of rural life now carry the weight of memory and loss.

“Greek visitors always say two things,” Kyparissis notes. “First: ‘This looks just like grandma’s house.’ Then, almost inevitably: ‘We had one of these – and we threw it away.’ And honestly,” he adds, “your heart breaks.”

The cellar, known as the ‘katoi’ in Greek, was traditionally used to store wine, olive oil, and other food supplies.

The cellar, known as the ‘katoi’ in Greek, was traditionally used to store wine, olive oil, and other food supplies. © Nikolas Sfantos

The cellar, known as the ‘katoi’ in Greek, was traditionally used to store wine, olive oil, and other food supplies.© Nikolas Sfantos

One of the museum’s most significant exhibits is a Columbia Grafonola phonograph that once belonged to Velonis. As a young man, he had left for America in search of a better life. Ten years later, he returned to his native village of Stavrinides – a walk along a cobbled path from Manolates – with his savings and a few treasured belongings, including the phonograph and a handful of Greek records made in the USA. It was a tangible fragment of Hellenism from the New World.

“That phonograph is a symbol of constant migration, of the struggle people face to stand on their own feet and maintain a livelihood,” Kyparissis explains. “It also represents Greek identity – an identity shaped by movement, by the ebb and flow of people and culture.”

The kitchen, featuring a fireplace and a gas cylinder-powered oven.

The kitchen, featuring a fireplace and a gas cylinder-powered oven. © Nikolas Sfantos

The kitchen, featuring a fireplace and a gas cylinder-powered oven.© Nikolas Sfantos

After his wedding and move to Manolates in 1924, Velonis worked as a vine-grower and wine merchant. Manolates was no stranger to class divisions, and Velonis – like his wife’s family – belonged to one of the few well-off households in the village. He became a landowner, thanks to the money he brought back from the US, and employed farm laborers. Velonis’ fortune came to an abrupt end with the Axis occupation, plunging him back into the hardship he had once escaped. In May 1941, Samos came under Italian control, with the 6th Infantry Division “Cuneo” stationed on the island. That winter, the Great Famine devastated Samos, killing over 2,000 residents and forcing thousands more to flee.

Velonis’ wine cellars were looted repeatedly by the Italian forces, trade ground to a halt and life deteriorated under occupation. One of his daughters died of syphilis during this period. Although he resumed his work in the vineyards after the war, it was an ordeal that contributed to his early death.

“In a way,” Kyparissis reflects, “this house shows that people often share a common fate – a fate not unlike Velonis’ own.”

A portrait of Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), a prominent Greek statesman of the early 20th century. Next to it, a porcelain cup bearing the green sun emblem of PASOK, Greece’s social democratic political party.

A portrait of Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), a prominent Greek statesman of the early 20th century. Next to it, a porcelain cup bearing the green sun emblem of PASOK, Greece’s social democratic political party. © Nikolas Sfantos

A portrait of Eleftherios Venizelos (1864-1936), a prominent Greek statesman of the early 20th century. Next to it, a porcelain cup bearing the green sun emblem of PASOK, Greece’s social democratic political party.© Nikolas Sfantos

That shared sense of destiny becomes even more powerful when objects in the museum begin to engage visitors in a kind of dialogue.

“When you show someone the phonograph and explain its story, it stops being just an artifact. It becomes part of the owner’s identity. And then a visitor might ask, ‘Did many people emigrate to America in the 1920s?’”

Another such item is a delicate greeting card from the Italian army, discovered in the nearby village of Mytilinioi. Italian troops distributed blank cards to their soldiers, who wrote greetings and sent them home via military mail.

“A visitor might come across that card and suddenly realize that this isn’t just Samos’ story; it’s part of something bigger. Whether they come from Germany, Italy, Australia, Canada, Turkey, or the Middle East, visitors begin to see how the story of Samos connects to their own.”

“And that,” Kyparissis says, “is the moment someone feels, ‘I exist in this story too.’”

2 months ago

80

2 months ago

80

Greek (GR) ·

Greek (GR) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·