Well, it’s official: Greek summer is here – and for anyone who loves food, that means one thing. A trip to the coast, a shaded table at a taverna, and a hearty spread of grilled sardines, golden-fried calamari, catch-of-the-day, and a cheeky glass of ouzo.

But this love affair with seafood isn’t just a modern Greek phenomenon. Our ancient forebears were just as enthusiastic about Poseidon’s pantry, but they took things further – much further. For the ancient Greeks, one of the most prized condiments at the table wasn’t lemon or olive oil, or a sprinkle of coarse sea salt, it was a fermented fish sauce known as “garon” (Greek: γάρον) – the pungent ancestor of what the Romans would later call “garum.”

Made from fermented fish and salt, this savory, salty liquid was ladled over just about everything: meat, vegetables, pulses – even wine. In its time, it was as ubiquitous as ketchup or soy sauce is today. Its smell, some said, could empty a room, but its taste was utterly addictive.

Here, we’ll explore the rise (and funky aroma) of garum in the ancient Greek world – how it was made, why it became a kitchen staple, how it traveled the Mediterranean in specially-made transport jars (amphorae), and how, with a little bravery, you might even try making your own batch at home.

According to some ancient sources, the fermentation process could last several months.

According to some ancient sources, the fermentation process could last several months. © Shutterstock

According to some ancient sources, the fermentation process could last several months.© Shutterstock

What Was Garum – and How Was It Made?

At its core, garum was a liquefied sauce created through the fermentation of fish and salt. The process was deceptively simple: take whole fish and/or innards (typically small, oily varieties like anchovies, sardines, mackerel, or sprats), layer them with coarse sea salt in large vats or ceramic jars and leave them in the sun for several months. As the mixture broke down, it became a briny slurry. The rich amber-colored liquid (“liquamen” in Latin) that rose to the top – carefully strained and bottled – was the prized result: garum. The paste-like sediment that remained was called “allec” and was sold more cheaply, often used by lower classes to season everyday dishes like oatmeal, pancakes (“tiganites”) or stews.

Though we often associate it with the Romans, this intensely flavored sauce has earlier roots in the Greek world. The word “garon” appears in Classical Greek literature centuries before the spread of Roman cuisine. Writing in the late 4th century BC, Aristophanes, in his comedy “The Wasps” (line 508), famously mocks Athenian excess with the line: “He’s so rich, he even puts garon on his lentils!” – a nod to its status as a luxury condiment among the upper classes.

The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder, writing later in his “Natural History” (31.93), described garum as “a putrid liquid made from fish,” yet admitted it was held in high regard, and acknowledged its Greek roots. He notes that the Greeks had long traditions of preserving seafood, especially through salting and fermentation.

Fresh fish, one of the favorite dishes of the ancient Greeks. Red-figure platter, ca. 350–325 BC.

Fresh fish, one of the favorite dishes of the ancient Greeks. Red-figure platter, ca. 350–325 BC.

Fresh fish, one of the favorite dishes of the ancient Greeks. Red-figure platter, ca. 350–325 BC.

Fresh fish, one of the favorite dishes of the ancient Greeks. Red-figure platter, ca. 350–325 BC.

Salted sardines and anchovies were regular fare for the ancient Greeks, especially those who lived inland and away from the coast.

Salted sardines and anchovies were regular fare for the ancient Greeks, especially those who lived inland and away from the coast.

Salted sardines and anchovies were regular fare for the ancient Greeks, especially those who lived inland and away from the coast.

Salted sardines and anchovies were regular fare for the ancient Greeks, especially those who lived inland and away from the coast.

So, where did the Latin word “garum” come from? There’s an etymological connection to the Greek word “garos” (γάρος), which referred to a small fish or shrimp – possibly the sauce’s original base. Intriguingly, the modern Greek words for anchovy (“gavros” – γαύρος) and shrimp (“garida” – γαρίδα) suggest a linguistic continuity. In ancient Greek, the suffix “-on” rendered a word into a concrete noun – so “garos” (a fish) became “garon” (a product made from it), which was later Latinized as “garum.”

Wherever it originated, production wasn’t confined to one region. Sites across the ancient Greek world – from Crete and the Cyclades to the Black Sea coast – have yielded tantalizing evidence of fish-salting operations with large stone vats, distinctive-looking amphorae, and chemical residues consistent with fermented fish products.

Despite its somewhat unappealing description, garum was considered a delicacy, praised not only for its taste but also for its ability to enhance and balance other flavors. Much like modern fish sauces from Southeast Asia – think Laotian “padaek” and Thai “nam pa” – or Britain’s tangy “Worcestershire sauce,” a little went a long way.

The "Deipnosophistae" by Athenaeus belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the Greek banquet, or symposium. Attic red-figure bell-krater by the Nikias Painter, ca. 420 BC.

The "Deipnosophistae" by Athenaeus belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the Greek banquet, or symposium. Attic red-figure bell-krater by the Nikias Painter, ca. 420 BC.

The "Deipnosophistae" by Athenaeus belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the Greek banquet, or symposium. Attic red-figure bell-krater by the Nikias Painter, ca. 420 BC.

The "Deipnosophistae" by Athenaeus belongs to the literary tradition inspired by the use of the Greek banquet, or symposium. Attic red-figure bell-krater by the Nikias Painter, ca. 420 BC.

Garum in Greek Life and Medicine

In ancient Greece, garum was enjoyed across all social strata, with different blends tailored to context. In humbler households, lower-grade fish sauces (“allec” paste or the simpler “liquamen”) were combined with herbs, oil or vinegar to add richness to stews, pulse dishes and vegetables. In higher status kitchens, premium grade, aged garum was sometimes mixed with wine, honey or spices, and used sparingly as a marker of refined taste.

The Greek grammarian Athenaeus (late 2nd–early 3rd century AD), in Book 2 of his “Deipnosophistae” (literally: “dinner-table philosophers”), quotes various gastronomes enthusiastically extolling fish sauce – including the Greek-Sicilian poet Archestratus (mid-4th century BC), who regarded garum as essential to elite fine dining. He describes a dish where the sauce is to be added “by the drop” and mentions its pairing with eel – a reminder that it was a powerfully concentrated ingredient: less a splash, more a whisper.

Garum, however, wasn’t just for food – it had medicinal uses as well. The Greek physician Galen, writing in the 2nd century AD, mentions garum in his “De alimentorum facultatibus” (III.41), describing it as “warming” and useful for “loosening the bowels” when consumed in moderation. Pliny, ever the encyclopedist, includes it in his “Natural History” as a treatment for ulcers, dysentery, and even dog bites. Some accounts suggest it was sipped diluted in wine or added to lentils as a tonic. It was even applied externally to remove freckles or unwanted hair.

Ancient Roman garum factory in Salga, modern-day Portugal.

Ancient Roman garum factory in Salga, modern-day Portugal.

Ancient Roman garum factory in Salga, modern-day Portugal.

Ancient Roman garum factory in Salga, modern-day Portugal.

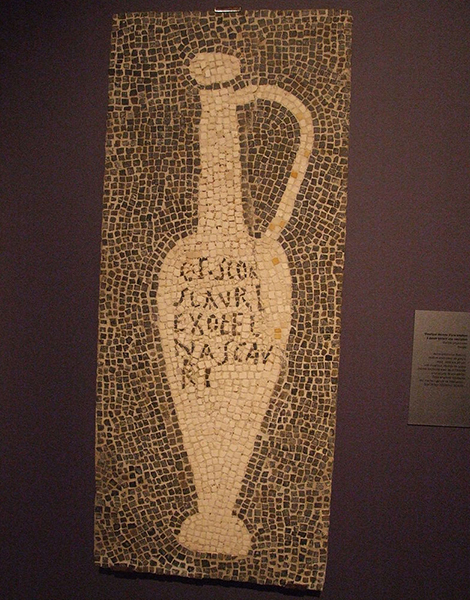

Mosaic depicting a "Flower of Garum" jug with a titulus (label) reading "from the workshop of the garum importer Aulus Umbricius Scaurus," Pompeii.

Mosaic depicting a "Flower of Garum" jug with a titulus (label) reading "from the workshop of the garum importer Aulus Umbricius Scaurus," Pompeii.

Mosaic depicting a "Flower of Garum" jug with a titulus (label) reading "from the workshop of the garum importer Aulus Umbricius Scaurus," Pompeii.

Mosaic depicting a "Flower of Garum" jug with a titulus (label) reading "from the workshop of the garum importer Aulus Umbricius Scaurus," Pompeii.

A Pan-Mediterranean Trade Network

For a condiment that began life as mushy pile of decomposing fish, garum has left behind a surprisingly rich archaeological footprint. While large-scale industrial production is best attested from the Roman period, particularly in Spain (Hispania) and North Africa, the groundwork for preserving and trading processed fish began earlier – and the Greeks were part of that story.

In the Greek world, we find evidence for fish salting and preservation, especially from the Classical and Hellenistic periods. On Delos, archaeologists have uncovered stone tanks and drainage channels, which may have been used for cleaning and salting fish, in association with the commercial quarters adjacent the harbor. Near Itanos in eastern Crete, similarly designed vats and concentrations of fish bones point to small-scale processing activity. Though these sites show no direct evidence of garon production, they reflect a broader culture of fish preservation – including salting, drying, and possibly pickling – that would later underpin Roman fermentation practices.

What’s lacking in the Greek archaeological record is clear-cut evidence for fish sauce production on the scale of Roman garum. In contrast, Roman sites like those at Baelo Claudia in Baetica (modern southern Spain) feature purpose-built “cetariae” – stone fermentation vats – and are found alongside amphora kilns and garum-branded exports. These facilities reflect a level of industrial organisation not (yet) seen in the Greek world.

Ruins of a garum factory in Baelo Claudia, southern Spain.

Ruins of a garum factory in Baelo Claudia, southern Spain.

Ruins of a garum factory in Baelo Claudia, southern Spain.

Ruins of a garum factory in Baelo Claudia, southern Spain.

Once produced, fish sauce was typically shipped in tall, narrow-necked amphorae with pointed bases – ideal for stacking in the holds of cargo ships. In the Roman era, these amphorae were often sealed with pitch or resin and bore painted labels (“tituli picti”) or stamped handles indicating contents, quality and workshop origin – an early form of branding and quality control.

Shipwreck archaeology adds important evidence. Amphorae with traces of fermented fish products have been recovered from wrecks near Rhodes, Chios, and in the Black Sea, often found alongside wine jars, oil containers and salted fish. These finds suggest a multi-commodity maritime economy, in which fish products – including garum – were part of broader trade networks linking the Greek world with Roman markets and beyond.

Although the largest garum-producing centers emerged in the western Mediterranean during the Roman period, amphorae types such as Dressel 7–11 type (1st century BC to 3rd century AD), commonly associated with fish sauce transport, have been found across the eastern Mediterranean as well. One practical rule seems to have held true throughout: garum was never stored or shipped in amphorae used for wine or oil – its pungent aroma would have spoiled an entire cargo.

Make Your Own Ancient Greek Fish Sauce

Intrigued? Well, if you’re feeling brave – and have very forgiving neighbors – why not try making your own version of ancient garum at home? All you need are fresh anchovies or sardines, plenty of coarse sea salt, and a little patience.

Using a clean glass or clay jar, layer the fish with salt at a 3:1 ratio (three parts fish to one part salt). For authenticity, leave the guts in – they help trigger the enzymatic breakdown that produces the savory liquid. Add a few aromatics if desired – bay leaf, oregano, or a splash of vinegar or honey – then seal the jar tightly and let the magic (or mayhem) begin!

Leave it in a warm, sunny spot for 7 to 10 days (ancient methods sometimes fermented for up to three months), stirring occasionally with a wooden spoon. Once a dark, fragrant liquid rises to the top, strain it carefully through cheesecloth or a fine mesh sieve and bottle the liquid. Congratulations! You’ve just made your first batch of homemade garum.

Caution: Home fermentation carries serious food safety risks, especially when working with raw seafood. Consult reliable sources or microbiological guidelines before consuming – or, like many ancient diners, leave it to the professionals.

Used sparingly, garum can transform a dish. Mix it with olive oil and drizzle over grilled vegetables, lentils, or warm bread for a deep, savory kick that recalls the kitchens of ancient Athens – the “umami” of Greek antiquity.

It may not be pretty – but to the ancient Greeks, it was the unmistakable taste of the sea.

1 day ago

5

1 day ago

5

Greek (GR) ·

Greek (GR) ·  English (US) ·

English (US) ·